The Litigation Landscape

Cauda Equina Syndrome (CES) is increasingly at the centre of high-value clinical negligence claims. The failure to diagnose and treat CES promptly can have life-changing consequences, often resulting in multi-million-pound settlements.

Recent high-profile cases include:

- Stewarts Law securing a seven-figure settlement.

- Outer Temple Chambers obtaining a multi-million-pound settlement.

There are Learned Society guidelines, e.g. BASS, Standards of Care for Investigation and Management of Cauda Equina Syndromeand more recently GIRFT, ‘National Suspected Cauda Equina Syndrome Pathway,and even a National investigation and suggestions for improvement by HSSIB but it was not known whether any of these attempts to reduce the incidence of this problem have made a difference. The report of the Committee of Public Accounts presented to the House of commons suggests these measures have not reduced spending on litigation and by deduction therefore on reducing its incidence.

As recognised spinal experts we reviewed a number of negligence cases involving CES. Some common themes emerge which may not be brought to the surface in investigations. A systems approach frequently falls short of analysing factors which may not be immedialy apparent in individual cases but which begin to emerge when several consecutive cases are studied.

The Medical Perspective: Why Does CES Get Missed?

Diagnosing CES early is notoriously tricky. The condition is uncommon, and its initial symptoms often overlap with those of benign back ailments, which can lull clinicians into false reassurance. For example, a patient developing CES usually has severe back pain and sciatica, but these are ubiquitous complaints in primary care and emergency departments. Early CES can mimic a routine case of sciatica or a slipped disc, so the rare patient who is actually harbouring a compressive cauda equina lesion may not be immediately distinguished from the thousands who are not. As one safety investigation noted, many CES patients experience multiple healthcare visits before the diagnosis is finally made. During those visits, subtle red flags may be missed if the provider attributes symptoms to more common conditions, such as simple sciatica, musculoskeletal back pain, or a urinary infection.

A key diagnostic challenge is that clinicians historically relied on classic “red flag” signs of CES, yet many of those signs actually indicate late-stage, irreversible damage. By the time a patient has frank urinary retention or faecal incontinence (traditional red flags), the cauda equina nerves may already be irreparably injured. In a 2017 analysis of guidelines, researchers found that one-third of so-called CES red flags were actually “white flags”, signs of defeat indicating late CES that likely cannot be fully reversed. For instance, loss of bladder/bowel control and absent perineal sensation were emphasised in older guidance, but these often appear only after significant nerve destruction has occurred. The study concluded that guidelines needed to shift focus to earlier indicators of CES essentially, warning signs of impending CES rather than waiting for the complete syndrome to declare itself. In practice, this means symptoms like bilateral sciatica, new urinary difficulties (hesitancy, retention or change in flow, an episode of incontinence), saddle-area numbness or tingling, and bilateral leg weakness must be taken seriously as potential CES even if the patient is not yet incontinent. These are the subtle red flags referred to above. Waiting for “textbook” CES is a recipe for missing the window for intervention.

Moreover, patient factors and system delays contribute to missed diagnoses. Patients may underreport or not appreciate the seriousness of early symptoms like urinary hesitancy or numbness (“I just thought it was a pulled muscle”). If sent home without clear warnings, they might only return when catastrophic symptoms develop. On the system side, accessing urgent MRI scans, the definitive diagnostic test for CES, can be challenging, especially outside of business hours. A hospital without 24/7 MRI might require transfer of a patient to another facility, causing precious hours of delay. Miscommunication between departments (ED, radiology, spinal surgery) can also slow the pathway. In short, diagnosing CES is a race against time complicated by subtle beginnings, human error, and logistical barriers.

Variation in Examination Standards

A diagnostic hurdle is the variable quality of neurological examination and documentation. Identifying CES relies on detecting subtle neurological deficits, symptoms and signs. Yet in many negligence case reviews, it becomes evident that examinations were either not done thoroughly or not documented clearly or done at all. Busy emergency departments might not always perform a complete sacral nerve examination (for example, testing sensation around the perineum or checking anal tone and reflexes). Even when such an examination is done, the findings are often recorded inconsistently, sometimes simply noted as “neurology NAD (no abnormality detected)” without specifics. A lack of detail can be critical: differentiating early CES from a simple backache might hinge on noting a patch of numbness or reduced anal reflex that requires careful, focused examination. Poor documentation also makes it harder for subsequent providers, or later medicolegal reviewers, to understand the patient’s evolving neurological status.

In some CES claim investigations, it has been found that neurological findings were missing or illegible in the notes or recorded with non-standard terminology that caused confusion. For instance, nursing staff might use unofficial terms or scales for muscle strength, and doctors might omit comparing left versus right sensation so a subtle unilateral perineal numbness cannot be later differentiated from bilateral saddle anaesthesia. All of these factors represent a systemic shortfall in examination standards. Performing and recording a proper neurological examination for any patient with possible spinal pathology is essential, yet this basic skill often falls short in the hectic real-world setting of front-line care, with even senior clinicians occasionally neglecting it.

Dysfunctional Teams

When a group from NASA were asked to define a team they came up with this. ‘A group of people working cooperatively towards a shared goal’ It might be assumed that this was a given in any hospital or primary care setting. The records of negligence cases suggest this is not the case. There do not appear to be ward rounds anymore where a Consultant and a group of individuals looking after an individual patient see and discuss that patient at a point in time. Notes are made on patients e.g. by a physiotherapist but clearly not read by the treating physician otherwise it would have been acted on but was not leading to catastrophe. Valuable information clearly stated in the records is ignored. Ambulance records readily available since they are automatically transferred electronically these days again containing valuable information not read by A&E. Notes are only of value if they are read by successive health providers. Hand written notes are frequently inaccurate or illegible. These are just a few examples of dysfunctional teams.

Anatomical description of pain location

Human anatomy is well described. There are several internationally recognised text books on the subject e.g. Gray’s Anatomy. The glossary outlines the anatomical parts of the upper and lower limbs. When a pain is described as neck pain going down the arm what does that mean? Which side is involved? Does it literally mean the whole of the upper limb or just that part which accurately describes the part between the shoulder and the elbow. Does low back pain with sciatica tell us where in the lower limb pain is located or left or right? These are vital observations in the history yet frequently in these negligence cases inaccurately documented.

The spine has four regions the cervical, thoracic, lumbar and sacral regions. Is low back pain high in the lumbar region or low in the lumbar region? A patient constantly complains of thoracic pain eventually becoming paraplegic from his discitis yet has his lumbar spine scanned. Nothing to explain his symptoms was found. It was not until he became paraplegic and a neurologist suggested an MRI scan of the thoracic spine his discitis was diagnosed. This is only known because the case crossed my desk.

Admission Policies

A third common theme is the placing of spinal patients on general surgical or medical wards. There may be comorbidities which drive the admission to these specialties. Where a spinal problem is clearly present/suspected the best place for that patient is on a spinal speciality ward. Of course many hospitals do not have spine as a specialty or neurology or neurosurgery as specialist areas. In that event orthopaedic care would seem to be the best option. It appears that this may only be the best option where there is a Consultant with a special interest in spinal issues. Finding beds in the correct speciality is frequently not possible in hospitals receiving acute cases. If all spinal cases were sent to tertiary spinal units they would be overwhelmed with many patients who do not need to be there.

- The Role of Clinical Pathways The Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) CES pathway aims to streamline diagnosis.

- How many frontline clinicians are aware of this? Is it realistic in busy A&E or GP settings for those clinicians to look at guidelines when dealing with a patient during a consultation? An individual GP may see one suspected CES case in a lifetime practice. An A&E specialist possibly several, but these cases are frequently initially seen by junior trainees, who may just be passing through.

- While these pathways may be read by those who have the responsibility of managing significant numbers of these cases e.g. a specialist spinal centre why would a GP access these guidelines when they will see a multiplicity of cardiac, chest, gynaecological and other much more common medical problems and try to keep abreast in those fields.

The Legal Perspective: When Does a Delayed Diagnosis Become Negligence?

- Breach of Duty and the Bolam Test.

- This is summarised as follows (Bolam v Friern [1957] 1 W.L.R. 583, 587) “I myself would prefer to put it this way, that he is not guilty of negligence if he has acted in accordance with a practice accepted as proper by a responsible body of medical men skilled in that particular art . . . Putting it the other way round, a man is not negligent, if he is acting in accordance with such a practice, merely because there is a body of opinion who would take a contrary view.”

- This means in the case of a delayed diagnosis of CES each individual who had contact with that patient has to considered. Where e.g. an individual fails to make the diagnosis because of a failure to properly examine the nervous system and record those findings but would have been expected to carry out such an examination and to reach the conclusion of possible CES then that may fall below an expected standard of care.

The Impact of the 4-Hour MRI Standard

- Current GIRFT guidance mandates MRI within four hours for suspected CES.

- Many hospitals lack 24/7 MRI access, particularly in District General Hospitals.

- Now that the four-hour rule is formally documented, will this fuel further litigation?

- Where does this leave the individual who documents that an MRI needed to be done but the system is not geared up to meet that standard?

- The resource implication of this standard needs to be addressed.

Financial Risks of Delayed Diagnosis

- With CES payouts often exceeding £3 million, the financial implications are severe.

- Could investment in round-the-clock MRI availability be more cost-effective than litigation costs?

What Needs to Change?

- Standardising Neurological Examination

- Should there be a clear, universal protocol for CES assessment?

- Would better training reduce diagnostic errors and improve legal defensibility?

- There is currently no structured process for learning from CES claims.

- How can hospitals ensure medicolegal insights drive clinical improvements?

- Should there be a clear, universal protocol for CES assessment?

The Future of CES Litigation

- The risk of CES-related negligence claims is escalating.

- Without greater standardisation in neurological examination and MRI access, litigation is unlikely to decrease.

Even with clear red flags and pathways, things can and do go wrong in the real world. Medicolegal case reviews and safety investigations have revealed recurring failure points in the CES diagnostic and treatment pathway. Understanding these can help us formulate recommendations to plug the gaps. Below is a conceptual framework tracing how a CES case might slip through the cracks, and what could be done at each stage:-

1. Initial presentation – Recognition failure: The patient’s first medical contact (GP or A&E triage) may not recognise the early signs of CES. Perhaps the patient complains of severe sciatica and some “trouble peeing,” but the significance isn’t appreciated. The clinician might focus on the back pain and diagnose a pulled muscle or sciatica, missing subtle neurological cues. Furthermore, CES assessment is frequently left to the most inexperienced member of the team who are the least equipped to assess an undifferentiated patient. Junior doctors, Physicians Associates and Advanced Care Practitioners form the bulk of those who assess patients with a condition where even the definition of the condition is highly nuanced. It is not uncommon to encounter a litigation case where, despite several attendances to ED, the patient was never assessed by a senior clinician. This failure then permeates to every other mode of failure such as a junior doctor requesting the MRI scan and accepting the radiographers explanation that the scanner is ‘busy’. Recommendation: Heighten clinical suspicion for CES in any back pain case with atypical features, however mild. Medical providers should explicitly check for red flag symptoms (ask about urinary changes, saddle numbness, bilateral leg symptoms every time severe back pain or sciatica presents). If patients have any possible CES indicators, even if mild, they should be warned that these could herald CES and given safety-net advice to return if they worsen. CES cases warrant senior clinical decision-makes input throughout similar to other serious cases such as major trauma.

2. Examination and documentation – Incomplete neurological assessment: Failing to perform a thorough neuro examination, or failing to record it, is a common pitfall. Time pressures or lack of experience can lead to cursory exams. For example, not checking perineal sensation (which can be awkward for patient and doctor) might cause missed saddle numbness. Or not testing anal tone might miss an important finding (though anal tone can be variable; it might still be drastically reduced in CES). In some negligence cases, the absence of a documented exam was itself a breach of duty, since a “responsible body” of doctors would agree that examining for CES red flags is standard care. Recommendation: Implement a standardised neuro exam protocol for back pain presentations. This could be a simple checklist: e.g., “Does the patient have normal sensation in the perineal area? Can they feel pinprick around the anus? Are anal reflexes present? Any weakness in foot dorsiflexion or ankle reflexes? Bladder distended?” By making this a routine part of assessment (and perhaps an electronic template in notes), clinicians are prompted every time. Improving documentation, using standard terms and even electronic forms, would not only improve care continuity but also provide medicolegal protection (“if you didn’t write it, it didn’t happen”). The idea of a national data set or template for spinal neurological exam has been suggested to ensure consistency. Regular training and refreshers in neurological examination for all doctors (especially those in emergency and primary care) is also crucial. After all, one cannot diagnose what one doesn’t look for.

3. Referral and handover – Delay in escalation: Let’s say a GP does suspect CES, the next step is urgent referral to hospital. Here, delays can occur in various ways. The GP’s urgency may not be conveyed clearly to the hospital (“patient has back pain with some signs of CES, please assess” might not communicate the true emergency). At the emergency department, triage might not appreciate the gravity if it’s not well-communicated, or if the patient’s symptoms are subtle at that moment. There can also be confusion over who should take ownership: should the patient be admitted under orthopaedics/spinal surgery straight from ED? Or should ED obtain the MRI first? Such unclear pathways cause a dangerous ping-pong of patients. This is of particular importance when up to 90% of such patients end up with negative scans, despite having urogenital symptoms which the orthopaedic team themselves may not be best placed to manage; a negative scan does not mean the symptoms have disappeared. There remains uncertainty between ED and orthopaedics about who is responsible for the patient with possible CES. Recommendation: Every hospital should have a clear SOP (Standard Operating Procedure) for suspected CES defining roles: e.g., “ED triggers immediate MRI and consults on-call spinal team after a diagnosis has been confirmed”. Referrals to spinal centres before a diagnosis adds only delay with no actual benefit to patient care, but such practices are often used by ED’s and non-specialist centres as a false risk mitigation tool. The new GIRFT pathway encourages exactly this clarity, and some hospitals have developed posters and flowcharts to ensure juniors and all staff know the drill. Strengthening communication can shave off precious time e.g. GP’s send patients to ED rather than discuss with the orthopaedic team to accept the patient. No patient with true CES should be sitting in A&E waiting room for hours; they need priority as if it were an acute stroke or MI.

4. Imaging bottleneck – Limited MRI access: Once the patient is in a hospital setting, the biggest bottleneck is often getting the MRI. Many incidents show patients waited overnight or had significant delays because an MRI scanner was not available or a radiographer was off-duty. For example, a patient might arrive at 10pm, but the hospital’s MRI operates only 8am-8pm, so they are kept on bedrest until morning by which time irreversible damage may be done. These delays are so critical that the entire GIRFT initiative has targeted them, with the aim of providing out-of-hours MRI capability everywhere. Recommendation: In the short term, hospitals that lack 24/7 MRI must have a contingency plan, e.g., an agreement with a neighbouring hospital or an on-call radiographer list to call in. This might involve cost, but consider that a single large CES claim (often > £3 million in damages) could fund a lot of after-hours imaging support. In the long term, commissioners should evaluate the cost-benefit of investing in round-the-clock MRI availability versus the human and financial cost of missed CES. Another recommendation is to empower clinicians to pursue MRI without unnecessary preliminaries for instance, do not insist on a spinal specialist review before MRI in obvious cases; let ED request it immediately as per protocol. Every hour counts, so streamline the pathway such that when CES is on the cards, imaging happens fast. Monitoring time-to-MRI as a key performance indicator could drive improvement, much like door-to-needle time is tracked in strokes. This also requires a mindset change with most acute hospitals having access to MRI scans during the day but frequently prioritising elective planned scans ahead of emergency requests.

5. Post-imaging and surgery – Treatment delay: Even after a positive MRI, delays in treatment can occur. Sometimes there’s difficulty arranging emergency surgery at night (no surgical team immediately available, or needing transfer to a regional neurosurgical centre). Each hour waiting for decompression is an hour of continued nerve compression. Some cases show patients diagnosed in the evening who weren’t operated on until the next day. Recommendation: Treat CES decompression as high priority emergency surgery (which the GIRFT pathway now categorises it as). Hospitals and surgical networks should treat it akin to other surgical emergencies i.e., have an on-call team that can be mobilised. If a local hospital cannot do spinal surgery, there should be a direct protocol to transfer the patient (and the MRI images) immediately to a spine centre. Additionally, document reasons for any delay meticulously. If, for example, surgery is delayed because two other life-threatening emergencies were in theatre, that should be recorded. This not only improves transparency (for later review) but forces teams to consciously justify waiting, which can act as a deterrent to unnecessary delays.

6. Follow-up and missed opportunities: Another failure mode is when a patient doesn’t neatly fit the classic picture and is sent away, only to return worse. Perhaps an MRI was done and was negative for CES, so the patient is discharged but with ongoing symptoms that actually were due to another pathology (e.g., a high spinal lesion or an evolving condition that MRI missed early). If a patient has red-flag symptoms but a normal lumbar MRI, one must not dismiss the symptoms instead, consider whole-spine imaging or neurology consultation, because “there is no benign cause for a numb saddle area”. In other words, something is wrong, even if it’s not a disc at L5/S1. Recommendation: Maintain a broad differential. If lumbar MRI is negative yet the patient clearly has saddle anaesthesia or bladder issues, escalate the investigation (thoracic spine MRI? Could this be an inflammatory cause? etc.) rather than simply assuming all is well. Also, ensure robust safety-netting: the patient should know to come back immediately if any new symptom of CES appears or worsens, because sometimes a partial syndrome today becomes complete in days.

References

DHSC Annual Report and Accounts 2023

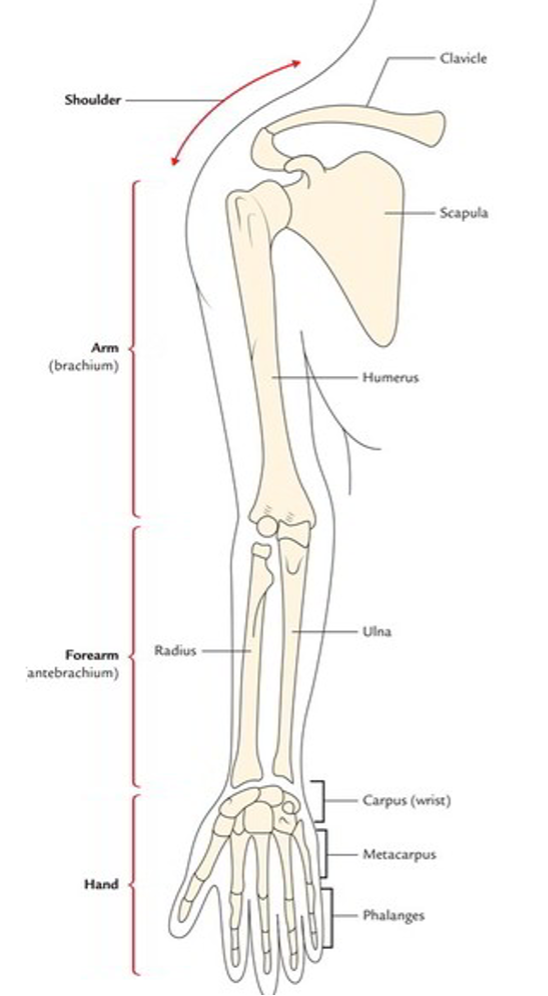

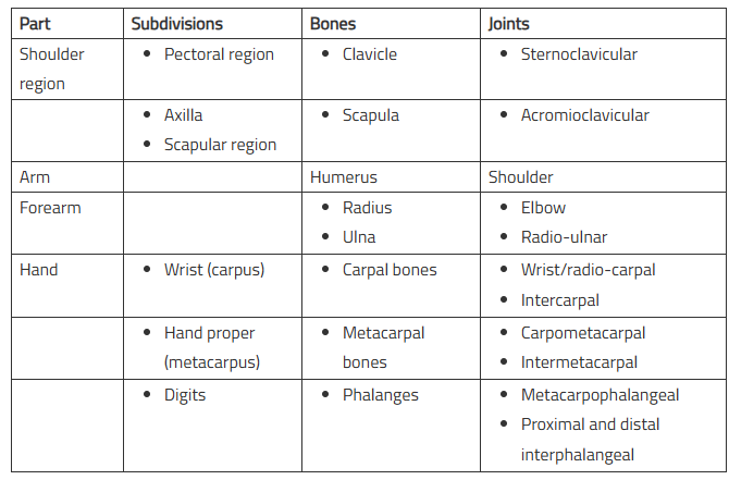

The upper Limb

The following are four parts of the upper limb;

- Shoulder.

- Arm or brachium.

- Forearm or antebrachium.

- Hand.

The shoulder region includes;

- Axilla or armpit

- Scapular region or parts around the scapula (shoulder blade)

- Pectoral or breast region on the front of the chest

The clavicle (collar bone) and the scapula (shoulder blade) are the bones of the shoulder region. At the acromioclavicular joint they articulate with each other forming the shoulder girdle. The shoulder girdle and the remaining parts of the body skeleton articulates with each other at the small sternoclavicular joint only.

The arm is the part of the upper limb between the shoulder and elbow (or cubitus). The bone of the arm is humerus, which articulates with the scapula at the shoulder joint and upper ends of radius and ulna at the elbow joint.

The forearm is the part of the upper limb between the elbow and the wrist. The bones of the forearm are radius and ulna. These bones articulate with humerus at the elbow joint and with each other forming radio-ulnar joints.

The hand (or manus) consists of the following parts:

- Wrist or carpus

- Hand proper (or metacarpus)

- Digits (thumb and fingers)

The wrist consists of eight carpal bones arranged in two rows, each consisting of four bones. The carpal bones articulate (a) with each other at intercarpal joints, (b) proximally with radius forming radio-carpal wrist joint, and (c) distally with metacarpal bones at carpometacarpal joints.

The hand proper consists of five metacarpal bones numbered one to five from lateral to medial side in anatomical position. They articulate (a) proximally with distal row of carpal bones forming carpometacarpal joints, (b) with each other forming intermetacarpal joints, and (c) distally with proximal phalanges forming metacarpophalangeal joints.

The digits are five and numbered 1 to 5 from lateral to medial side. The first digit is called thumb and remaining four digits are fingers. Each digit is supported by three short long bones-the phalanges except thumb, which is supported by only two phalanges. The phalanges form metacarpophalangeal joints with metacarpals and interphalangeal joints with one another. The first carpometacarpal joint has a separate joint cavity hence movements of thumb are much more free than that of any digit/finger.

The functional value of thumb is immense. For example, in grasping, the functional value of thumb is equal to other four digits/fingers. Therefore, loss of thumb alone is as disabling as the loss of all four fingers.

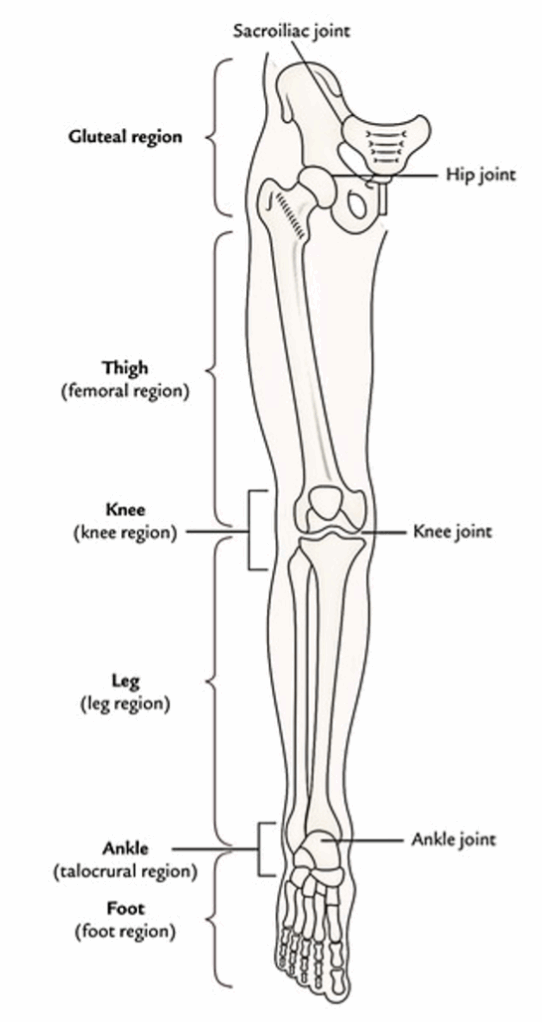

The Lower Limb

For illustrative purposes, the lower limb is split into 6 parts or regions:

- Gluteal region.

- Thigh or femoral region.

- Knee or knee region.

- Leg or leg region.

- Ankle or talocrural region.

- Foot or foot region.

Gluteal region

The gluteal region is located on the back and side of the pelvis. It is composed of 2 parts: the rounded notable posterior region referred to as buttock and lateral less notable region referred to as hip or hip region.

The buttock is bounded superiorly by the iliac crest, medially by the intergluteal cleft, and inferiorly by the gluteal fold. The majority of it creates the gluteal muscles. The hip region overlies the hip joint and greater trochanter of the femur.

Thigh or femoral region

The femoral region is located between the gluteal, abdominal, and perineal regions proximally and the knee region distally. The bone of the thigh is femur, which articulates with the hip bone in the hip joint and upper end of the tibia and patella in the knee joint.

The abdomen is demarcated from the thigh anteriorly by the inguinal ligament and medially by the ischiopubic ramus. This junction between the abdomen and thigh is named inguinal region or groin. The gluteal fold is the upper limit of the thigh posteriorly. The lower part of the back of thigh and back of the knee is referred to as ham (L. poples).

Knee or knee region

The knee region consists of bulges (condyles) of the femur and tibia, head of fibula, and patella (knee cap). The patella is located in front of the distal end of femur and medial and lateral femorotibial joints. The posterior aspect of the knee presents a well defined hollow termed popliteal fossa.

Leg or leg region

The leg region is located between the knee and ankle regions. The leg includes 2 bones: a long and thick medial bone- the tibia, and long and narrow lateral bone- the fibula. The bulge on the posterior aspect of the leg created by a large triceps surae muscle is referred to as calf (L. sura).

Ankle or talocrural region

The ankle region contains distal part of the leg, and bulges (malleoli) of tibia and fibula. The ankle joint can be found between the malleoli and the talus.

Foot or foot region

- The foot is the distal part of the lower limb. It includes 7 tarsals, 5 metatarsals, and 14 toe bones (phalanges). The superior outermost layer of the foot is referred to as dorsum of the foot and its inferior surface is known as the sole of the foot. The sole is homologous with the palm of the hand. The foot gives a stage for supporting the body weight when standing and plays a key function in locomotion.

- The foot has gotten maximum changes during development. In the lower primates (example, apes and monkeys), it’s a prehensile organ and grab the boughs with their feet.

They can oppose their great toes over the smaller toes. In individuals, the great toe comes to is located in keeping with other toes and loses its power of opposition. It’s considerably enlarged to supply primary support to the body. Its 4 smaller toes due to reduction of prehensile function have become vestigial and reduced in size. The tarsal bones have gotten large, powerful, and wedge-shaped to give stable support. - The 4 major parts of the lower limb are summarised in Table below. The basic structure of the lower limb is quite similar to that of upper limb, but it’s changed to support the weight of the body and for locomotion.

- The lower limb joins the pelvic girdle in the hip joint. This girdle is composed of the 2 hip bones which join anteriorly at the pubic symphysis and posteriorly with the sacrum in the sacroiliac joints. The lower limb is supported by the heavy bones. The femur (largest and strongest bone of the body) articulates superiorly with the pelvis in the hip joint and inferiorly with the upper end of tibia in the knee joint. The tibia and fibula joint with every other at proximal, intermediate, and inferior tibiofibular joints. The distal ends of these bones articulate together with the talus to create the ankle joint.

| Parts | Bones | Joints |

|---|---|---|

| Gluteal region (on side and back of pelvis) | Hip Bone | Sacroiliac joint |

| Thigh (from hip to knee) | Femour | 1. Hip joint 2. Knee joint |

| Leg (from knee to ankle) | 1. Tibia 2. Fibula | 1. Tibiofibular joints 2. Ankle joint |

| Foot (from heel to toes) | 1. Tarsals (7) 2. Metatarsals (5) 3. Phalanges (14) | 1. Intertarsal joints 2. Intermetatarsal joints 3. Metatarsophalangeal joints 4. Interphalangeal joints |